If a place can be defined as relational, historical and concerned with identity, then a space which cannot be defined as relational, historical and concerned with identity will be a non-place.Marc Augé, Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, London, Verso, 1995, p. 77-78.

This report is about a « new town » near Tianjin called Jingjin (京津新城). In this report, I will try to bring a few elements of analysis on this failed planning project.

A critique of the « ghost city » paradigm in urban China

Jingjin New Town, located in a remote area 45 km from Tianjin, was originally conceived as a high-standard suburbian paradise, planned in order to attract residents from the elite and the middle-class from both Beijing and Tianjin. Nicknamed « Asia’s biggest villa compound » by newspaper reports, it failed in its goal to become Beijing’s and Tianjin’s « exquisite » backyard. Instead, it turned into a strange urbanized environment: half-empty sidewalks, abandoned construction sites and half-built residential compounds characterized the landscape.

For many China experts, this situation of urban planning financed through overinvestment as a way for local governments to stimulate local growth, corresponds to the concept of « ghost city » (鬼城 in Chinese), which has spread in newspapers reports, but also in scholarly literature in urban studies in China, emphasizing the desolation and emptiness of these landscapes.

I admit that Jingjin New Town offers a strange landscape because of the contrast between the massive size of the built environment and the global feeling of emptiness and unfinishness. But the « ghost city » paradigm is problematic. First of all, it is a normative concept: the « ghost city » is understood as a « pathology » (Sorace and Hurst 2015). Other authors call these places « wasted cities » (He, Mol and Lu 2016). Secondly, it suggests a form of exceptionalism: the « ghost city » is a phenomenon unique to China, because the emptiness of the city comes in a reversed temporality from the usual lifecourse of cities. The abandoned phase happens at the beginning on newly built architecture, and not after a long period of decline (see Shepard 2015). A different perspective was adopted in photographer Kai Caemmerer’s project. The artist introduced the notion of « unborn cities ». This notion seems like a more accurate way to describe this phenomenon than the notion of « ghost city ». However, from only a visual perspective, any of these photographers’ photo projects focusing on the visual effect of these buildings imply an anomaly in the process of city-making.

I argue here in favour of the ordinary elements that produce this strange context, especially the political economy of land and real-estate markets in China (Woodworth and Wallace 2017). I suggest that, even in such a strange environment, social scientists can also study the ordinary « production of space », following Henri Lefebvre’s definition, especially through the way the local residents and workers use and re-use it.

In urban China, these under-inhabited places are never completely abandoned, there are still people living or working there. The archetype of the « ghost city » in China is illustrated by the new district of Kangbashi in Ordos (Inner Mongolia). Ordos attracted a lot of visitors, photographers, researchers who took hundreds of pictures of the eerie emptiness of these scarcely used buildings, especially the « white elephants » projects such as the city museum. But instead of calling the place a « ghost city », a more qualitative description of what is occuring in such a specific socio-spatial configuration can be more interesting. For example, the photography series by Raphael Olivier entitled « Failed Utopia », shows that the space is still used by a minority of ordinary people.

In this photo, you can see a strange contrast between the size of the building and the emptiness of the square. But an ethnographic look at this photo would focus on a person, who is not an extraordinary person: we can see a school kid, wearing his uniform. This can mean that there is a school nearby, with pupils. Indeed, Kangbashi has inhabitants:

[…] Kangbashi is […] an underpopulated urban region, and has not thrived to the extent that the municipal authorities once envisaged. Nevertheless, a process is now clearly underway, even in the most infamous of “ghost cities”, through which the residents of new cities are (re-)constructing senses of home […].

(Yin, Qian, and Zhu 2017)

Ordinary life is being invented and goes on in this strange landscape. Therefore, since the « contradictions » of Chinese urbanization are reflected in these failed new towns, it would also be interesting to wonder about how these failed projects are considered in the eyes of the local people’s more personal visions of the urban space and how they make this space (originally not planned for them) their own. What are the new daily uses and indigenous representations of such « failed » projects?

The absurdity of extreme rationality in Chinese urban planning…

Again, as an ethnographer, I do not use the popular notion of « ghost city » to characterize a place such as Kangbashi or Jingjin New Town. I believe these new districts constitute failed projects but that there is nothing really extraordinary in these urban spaces; there are inhabitants, workers, etc. The failure is noticeable because these kinds of places are under-populated and that the social standards of the current population are lower than originally expected in the plan.

Jingjin New Town project was ambitious and extremely rational in a way. It followed the objective of urbanization around the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei conurbation hub. According to these three cardinal points, Jingjin New Town would be located in the most rational of places, equally distant from three major big cities, Beijing, Tianjin and Tangshan. It represented the perfect location to guarantee effective capital accumulation through suburbanization (Jie and Wu 2016). The urban planning project expected to build 8,000 villas to attract a middle and upper-class population working in the big cities. As an exclusive newly-built residential space, it would offer them the ideal « good life » characterized by the material possession of a luxury villa, a car, in an area with children facilities, etc. The problem is that, the new town was equally far away from the three cities of Beijing, Tianjin and Tangshan. This is why in this case, the « perfect » location turns out to be not so perfect, especially when the new town is not equiped with a high-speed railway station, not even with a fast connection to either of these cities by public transportation…

Jingjin New Town as « non-place » (Augé)

The name of the new town, « 京津新城 », illustrates the impossibility to « make place », at least for the time being. Indeed, Jing and Jin respectively refer to Beijing and Tianjin, which are major cities in China. Therefore, on a symbolic dimension, the place seems to have no essence of its own. The dominant characters of other cities tend to make this place much less relevant, almost invisible, caught within the city-region paradigm of the « Jing-Jin-Ji » axis (Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei). In other words, it seems that Jingjin New Town is no more than an excrescence of two mega-cities. The incapacity to attract enough residents prevents it from becoming a « place » with its own identity. The question is, do the few locals manage to turn parts of it into a « place »?

The thematisation of spaces in urban China… and alternative spectacles of emptiness

According to Ren Hai, the theme park in China is not only conceived as a leisure facility, it is also a normative spatial entity where the aesthetical designs and daily uses aim at producing certain types of « civilized » behaviours (Ren 2007). The mechanisms of the theme parks thus reveal a new spatial economy of consumption and a new technology of control. But the thematization of urban spaces in China goes beyond the only case of theme parks and amusement parks. Indeed, this logic of thematization has been developing within Chinese urban planning to build more « ordinary » projects, such as residential compounds, holiday resorts, etc.

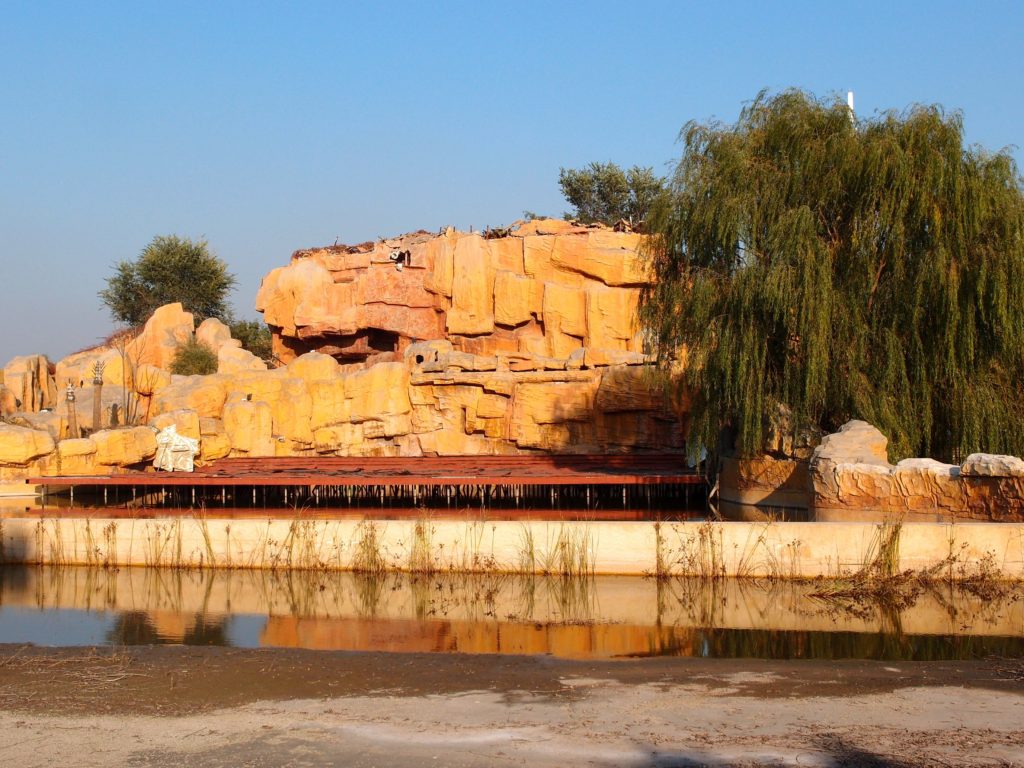

As you can see from this photo, the landscape of Jingjin New Town is highly thematized.

In our research, we will go deeper into this notion of themed space. What kind of landscape is produced when the project of themed space has failed? What is the new, alternative landscape produced in the current context of emptiness and unfinishness?

Half-inhabited residential compounds

The project was not just about building luxury villas. There are more ordinary housing compounds that have more inhabitants. Many of them are students who study in the local university branch.

The unfinished villas were the most critical elements brought up by the media about Jingjin New Town. Yet, again, not all the built villas were empty. I met a retiree who told me he was very happy with the house he bought. If the project had been « successful », he would not had been allowed to fish in the small canal or to raise farm birds and pigeons. But in the context of failure, he could did it, because the social control of behaviours in the compound was not implemented so strictly for just a few residents.

Therefore, there are modifications, adaptations by the local inhabitants, who still find ways to « make place » in this environment.

Disused playgrounds and leisure facilities

Apart from the few local inhabitants, the university students using the lower-standard housing compounds, going to the few restaurants, little shops (xiaomaibu in Chinese) and internet bars, most of the « exclusive » leisure facilities were abandoned when we visited Jingjin New Town.

According to a few gardeners, there were hot springs opened for the tourists during the summer, but I am not sure they ever opened.

During the visit, we could also find a disused snowpark.

There was also a disused waterpark with a lot of abandoned attractions.

Abandoned luxury villas as in-between spaces

The most interesting part of Jingjin New Town was the unfinished and abandoned compound of luxury villas. There is an atmosphere of incompleteness where the space opens up to unexpected functions: the built concrete structure mixes with the plants growing around, the empty rooms with their huge windows have a very interesting lightning effect on the walls, the flooded basements create eerie reflections on the water… This is why I call them in-between spaces. Another very inspiring photography series by artist Andi Schmied focused on this compound of unfinished luxury villas in Jingjin New Town, highlighting the interesting fusion of contrasting elements and the new social practices that emerged from the local workers and residents, appropriating the local space and enjoying the emptiness to create their own personal residential space or to invent their own hobbies there. The artist’s vision is presented in the article below:

I also visited that same villa compound. There is a sharp contrast between the project of this ultra-sophisticated housing form and its abandoned state, where grass and plants grow back on the built structure.

The house seemed finished from far away, but once we went inside, we realized that there was just the concrete structure, and that it had no decorative elements except for the windows.

The functions of the villas have been altered. Some of the houses were used as spaces to stock several architectural elements that were not installed around the villas yet.

Declining luxury: The Hyatt Regency Hotel and Spa Resort

Finally, there was a final element in the failed themed-space of Jinjing New Town: the Hyatt hotel. The Disney-shaped towers were visible from a distance but once we got closer, we realised it was really empty, even if it was still open to the public.

This hotel has an official website. This hotel was one of the biggest and emptiest buildings we had ever seen. It has 650 rooms and pretends to be offering its gests access to an icing rink and to a series of hot springs but most of these equipments were closed.

I hope to develop in the future months this first reflection on the way failed projects in China contribute to the production of in-between spaces, so let me know your feedback on this report… thanks in advance!

If you like this series, you can look at Burbex’s report on the same place here. If you like my series on failed projects in urban China, you can read my report about « little Paris » or « Tianducheng » in Hangzhou.

Bibliography

- Guizhen He, Arthur P. J. Mol, and Yonglong Lu, « Wasted cities in urbanizing China », Environmental Development, vol. 18, 2016: 2-13.

- Hai Ren, « The Landscape of Power: Imagineering Consumer Behavior at China’s Theme Parks », in Scott A. Lukas (ed.), The Themed Space: Locating Culture, Nation and Self, Lanham, Lexington Books, 2007: 97-112.

- Jie Shen, Fulong Wu, « The Suburb as a Space for Capital Accumulation: The Development of New Towns in Shanghai », Antipode, 2016.

- Wade Shepard, Ghost Cities of China: The Story of Cities without People in the World’s Most Populated Country, London, Zed Books, 2015.

- Christian Sorace, William Hurst, « China’s Phantom Urbanization and the Pathology of Ghost Cities », Journal of Contemporary Asia, 2015.

- Max D. Woodworth, and Jeremy L. Wallace, « Seeing ghosts: parsing China’s “ghost city” controversy », Urban Geography, vol. 38, no. 8, 2017: 1270-1281.

- Duo Yin, Junxi Qian, and Hong Zhu, « Living in the “Ghost City”: Media Discourses and the Negotiation of Home in Ordos, Inner Mongolia, China », Sustainability, 9(11), 2017.

Magnificent and eerie, poetic and uncanny. And yes, certainly troubling. A not-so-well-known face of China, even for me who lives there. Loved your article, thanks!

Thank for sharing this experience. Unborn town and yet not totally empty. Difficult to understand the reasons why such a giant project was abandoned, unfinished. I hope the old angler can go on fishing peacefully in this dreamy landscape.